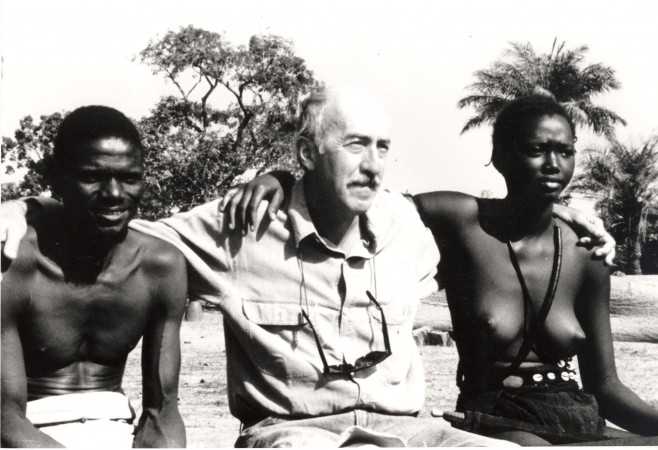

“What you give is yours, what you keep is lost,” goes one Georgian proverb. “Everything that happens in my films has to do with people’s weakness for possession,” says Otar Iosseliani. “And this leads to real values such as feelings disappearing.” One could add that all of the director’s films are about the disappearance of culture, sensuality, altruism and solidarity. They are poetic tragicomedies which feature a keen sense of humor, a slight wistfulness, reduced dialogue and flowing imagery. Born in 1934 in the Georgian capital Tbilisi, Otar Iosseliani studied music and math before taking a directing course in 1955 with Alexander Dovzhenko at the VGIK Film School in Moscow. His graduation filmAPRILI (1962), a critical examination of the petty bourgeois aspirations to possess, was banned in the Soviet Union. The film shows a strong affiliation for the films of Jacques Tati and already displays the distinctive features that would become so characteristic of his work. Like many of his later films,APRILI does not have extensive dialogue or commentary. Iosseliani is of the opinion that words should not be determining factors and should not hold any important information. In his works, the essential is revealed by facial expressions, gestures and the way the protagonists hold themselves. Words are equal to music and other noises on the soundtrack. After APRILI was banned, Ioselliani worked for two years as a fisherman, sailor and metal founder and these experiences are reflected in his short film TUDZHI (Cast Iron). In his first feature-length film, GIORGOBISTVE / LISTOPAD (Falling Leaves, 1966), he turns his attention to one of his most important leitmotifs. It is about a young idealist who tries to prevent the bottling of bad wine. For Otar Iosseliani, wine is not about gastronomy but about spirituality. “That’s why drinking wine is so important in my films. It brings people together, helps them to discover something new – maybe even happiness.” In his next two features, his film language reached new heights. Iko shashvi mgalobeli (Once Upon a Time There Was a Singing Blackbird, 1970) and PASTORALI (1975) adhere even less than his previous works to conventional dramatic form. “So as to correspond more to the free course of the flow of life” (O.I.) the form seems more like a musical composition. Subjects overlap, vary and are organized according to the rules of counterpoint. Intensified by the use of long shots that the director liked so much and a minimum amount of cuts, there is the impression of permanent circulation – everything flows. In 1982, Iosseliani emigrated to France after years of not being allowed to work by the Soviet authorities and the proscription of his film PASTORALI. However, he found himself confronting other problems: “In the West, one has to familiarize oneself with another type of censorship, which is particularly bad: the censorship of the audience which for generations has grown up with a particular taste.” Iosseliani has since made a dozen films, in Senegal, Italy, France and Georgia, which he all considers Georgian films. They talk about the poor and the rich, urban life and the country, traditions, the loss of values and the passing of time. They are at once melancholy and cheerful because “when things are taken very seriously it is hard to talk about them seriously (O.I.). They are fables in which there is singing, wine and cigarettes. Like a Georgian proverb goes, “he who neither smokes nor drinks will die very healthy.”